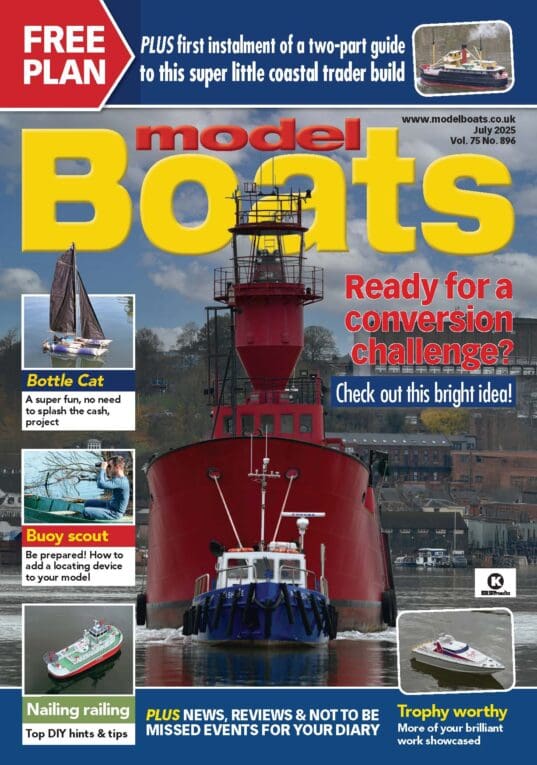

The ocean tugs of the US Navy’s Powhatan class, which entered service between 1979 and 1981, remain the most recent such vessels in the American fleet. Only the first two Nimitz class aircraft carriers have been operating longer, thanks to a round of costly life-extending modernisations. Meanwhile, these tugs have been quietly working for the last four decades essentially as they left the shipyard, with only minor updates over the years.

The concept

The Powhatan Class of fleet tug was conceived in 1974 as successors to the tremendously successful Navajo Class of W.W.II, the largest class of seagoing tugs ever built. As capable as the wartime tugs were, some of which are still in service with foreign navies after more than 70 years, in the Navy’s eyes they were underpowered, labour intensive and simply past their prime. The replacement tugs were designed to come to the aid of the largest ships in the modern fleet, towing them to safety over considerable distances if necessary. They were to have a thorough complement of salvage equipment, the capacity to carry larger deck loads, and be equipped with the latest in electronic automation.

Enjoy more Model Boats Magazine reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

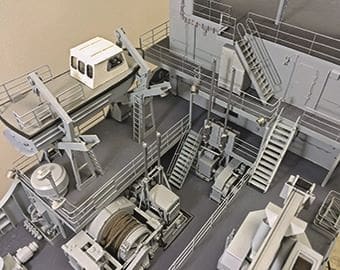

The Powhatan’s were a radical departure from the traditional design of their forebears. It was understood that the general layout of commercial offshore supply vessels was better suited to the Navy’s needs, so it was directed that the new tugs be arranged similarly with tall bows for good sea-keeping, a deckhouse located high and forward for superior visibility, and a broad fantail to facilitate a wide variety of tasks. These similarities were really only skin deep however, as the new tugs were designed from the keel up with naval requirements in mind. At 226 feet in length and 2260 tons displacement they were significantly larger than their predecessors and their twin EMD-20 diesels produced double the horsepower to allow them to extract the largest ships from the battle zone. To help deliver all that pulling power, they were equipped with controllable reversible pitch props, Kort nozzles and two separate towing winches, a synthetic rope traction winch for smaller tows, and a 2.25 inch wire rope automatic towing machine capable of handling anything afloat.

The new tugs also had extensive salvage and fire-fighting capabilities. A 9000 pound Moorfast anchor was located in the bow to facilitate de-beaching operations, and this could be augmented with powerful hydraulic pullers if extra persuasion was needed. The fantail was fitted with a grid of one inch bolt receptacles, allowing practically anything to be secured to the deck for special operations and a large stern roller was incorporated into the transom to permit heavy lifting and dive support. A 10 ton electro-hydraulic crane provided the same lifting capacity as the older tugs, but in a much more compact package and a bow thruster enabled precise positioning. Two diesel driven off-ship fire pumps supplied up to 2200 gallons of water and foam each minute and redundant external manifolds and hose stations provided even more fire-fighting versatility.

Despite all of this additional size and capability, the new ships required only a crew of 16, compared to the 70 plus persons needed to operate the older tugs. This reduction in manpower was largely as a result of automation, from an engine room that could operate unmanned, to a crane which required only one person at the controls (no more kingposts, winches and vangs). The propulsion systems of the T-ATF could be controlled from three separate locations: the engine room, bridge or from the winch control station overlooking the fantail. From this last station, the engines and props could be worked in concert with signals from the towing machines and commands from the winch operator, providing just the right amount of thrust at the right time. Even the Norman pins were hydraulically actuated, and could be raised or lowered at the touch of a button.

All these advancements came at a cost however. The Navy had originally planned for ten ships, but at $17 million each only seven were approved. Further savings were realised by transferring the completed tugs to Military Sealift Command, where they would be crewed by civil service mariners.

Construction

Marinette Marine Corporation of Marinette, Wisconsin was awarded the contract for the new vessels and the keel for the class leader was laid in September 1976. Construction of the first ship was plagued by delays, and USNS Powhatan (T-ATF-166) did not enter service until June 1979. Mind you, three more tugs, Narragansett, Catawba and Navajo, followed in quick succession. As this first batch of tugs was nearing completion work commenced on the remaining T-ATF’s approved for construction. Although all seven tugs appeared identical to the casual observer, the last three ships (Mohawk, Sioux and Apache) actually incorporated a host of small improvements over their earlier brethren the most noticeable of which was an extended forward breakwater to better shelter the anchor handling machinery.

All have proved to be invaluable additions to the fleet and are well suited to the myriad of tasks they were designed to undergo. Three of the tugs were removed from service as the fleet downsized in the late-1990’s: Powhatan now serves the Turkish Navy (which, coincidentally, still operates an old Navajo-class tug (the former USS Sioux, ATF-75) and Narragansett has been leased into commercial service. Only Mohawk sits inactive, held in reserve at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

The remaining four tugs, Catawba, Navajo, Sioux and Apache, have soldiered on with scarcely a reprieve for 37 years. Even so, the eminent retirement of these hardworking ships is looming. Plans are underway to replace the T-ATF’s with a combined towing and salvage vessel called the T-ATS(X). Although the design is not yet finalised, construction is scheduled to commence in 2018. The last Powhatan class tug will be relegated to history by 2024, but if the endurance of their predecessors is any indication, they are likely to serve their future owners for some time to come.

Service history

USNS Sioux (T-ATF-171) is the sixth of seven T-ATF’s, and entered service in May 1981. Her delivery voyage took her across the Great Lakes, down the East Coast, through the Panama Canal, and finally to her home port of San Diego in California. Since then, she has been engaged in countless operations throughout the Pacific; from routine movements of barges and naval craft, to clearing out the Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet by towing retired warships out to sea for use as missile, torpedo, or gunnery targets. Search, salvage and diving operations constitute much of her activities, whether on actual missions or conducting training exercises to keep her crew and diving detachment sharp. Aircraft recovery (both military and commercial) has been a frequent part of her repertoire, some of which have been salvaged from considerable depth.

Sioux often serves in a rescue capacity as well, coming to the aid of naval or civilian craft in distress. She once responded to an emergency involving the Canadian oiler HMCS Protecteur, which had lost all power after experiencing a serious engine room fire in the middle of the Pacific. The venerable tug departed Pearl Harbor with all speed, rendezvoused with Protecteur in the midst of a severe storm, and hooked up the tow in 12 foot seas. She and her charge arrived safely back at Hawaii after four arduous days, an effort that earned her the Canadian Forces Unit Commendation.

Her crew have no time to rest on their laurels however. She is at sea for more than 30% of each year, a rate of activity that most combatants struggle to attain, and though her efforts are often overshadowed by sleek new designs and the latest in naval technology, the hard-working tug continues to support the fleet in countless unsung ways, year after year.

Research

My education is in marine engineering, but I was an avid model maker long before I set foot on my first ship. I was fortunate to have served aboard the Sioux several years ago, and I knew that I would someday attempt a model of her even as I walked up the gangway. So, I made a point to document everything I could during my time aboard; taking roll after roll of photos (if only there were digital cameras back then!) and making photocopies of the set of plans that were aboard. I also accumulated a boxful of manuals for the various pieces of equipment, which proved to be a tremendous help later. The Chief Engineer was even kind enough to donate photos of the ship when in dry-dock.

I prefer my models to represent vessels as they left the shipyard, unmolested by time and modifications. Sioux had been in service nearly two decades by the time I was aboard, so I spent the next few years tracking down documentation from her earliest days, something which was no easy task. Eventually I turned to Marinette Marine for help, and they were able to provide a complete set of photos of the ship under construction and on sea trials. They even threw in some photos of the other T-ATF’s fitting out. Military Sealift Command helped fill in the rest of the blanks, with detailed scans of structural plans, equipment drawings, and system arrangements.

All in all, I was blessed to have probably the most comprehensive documentation one could ever ask for to help create a scale model; a feat I probably won’t be able to duplicate again. As it was, a full 12 years elapsed before I finally made a start on the model and another 3 years before it was actually complete.

TO BE CONTINUED…