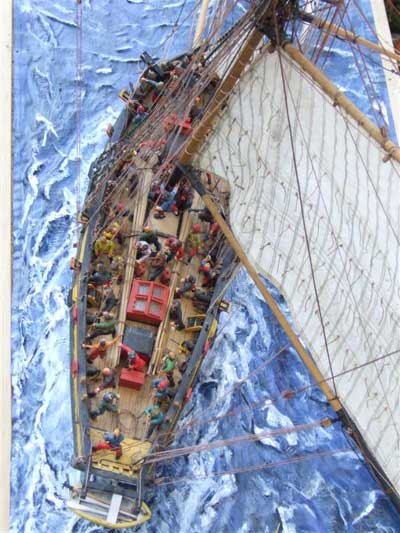

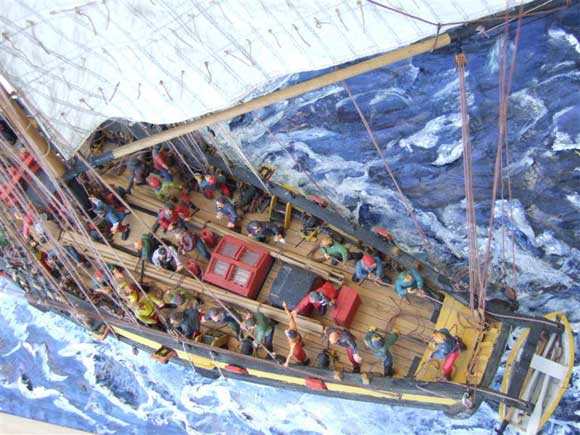

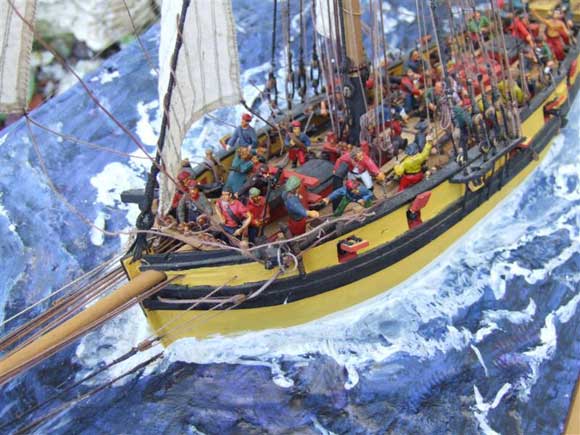

Pic 1: Port bow view from overhead. Pic 2: An overhead seagull view from above the stern.

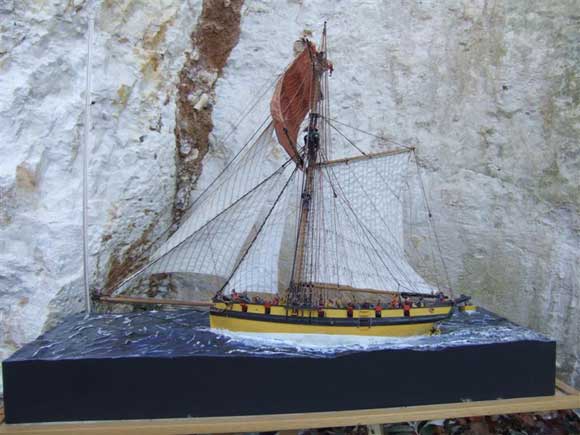

Pic 3: Le Renard at full speed. Pic 4: Close up on the mainmast top. Pic 5: Focus on the bowsprit with all the blocks required for amongst others, the top sail bowlines and braces. Pic 6: Focus on the topsail. It has been brown dyed to add some extra colour to the model. The traces of the glue used to mould the canvas, also give the feeling of wear and tear of the sail.

At the end of 1812 in the port of Saint Malo, Robert Surcouf ordered a 70 ton cutter specifically designed for high speed. This privateer, carrying ten 8pdr. carronades and four 4pdr. guns, was named Le Renard (The Fox). Under the command of Captain Leroux Desrochette and with an official letter of marque making the ship officially a privateer, Le Renard started her career in 1813. On 8th September she left for her second channel run.

Action in the Channel

Here is the subsequent report by Captain Desrochette, which gives an impressive description of the fierceness of the battle with the British Navy Schooner Alphea.

‘I had the honour to inform you that I dropped anchor yesterday evening in the bay of La Grande Anse, Diellette, back from my cruise. We left Batz Island on 8th September 1813, with a strong west wind and we crossed the channel during the night. The next morning at 4am we saw Start Point, four leagues away to the north west. At 3pm we saw a sail on our lee side and ran for it. At 5pm I realised that it was a British Navy schooner. I put about and she did follow and took chase, two leagues behind us. Within one hour she closed in and I ordered that we clear for action. She started the fight with her chase guns. She went about and I fired with my guns several broadsides into her at pistol range, with the additional support of all our musketry.

Enjoy more Model Boats Magazine reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

During the firing, my First Lieutenant Devose, as well as two Lieutenants Berhelot and Rameire, were all wounded, as well as a great number of my crew. The wind dropped off, although there was still a heavy swell, and the enemy drifted on our lee side. I ordered my crew to board her. Superior in number the enemy was able to fend us off, although with heavy losses and firing grape shots on to the whole forecastle. My executive officer got killed and I had some additional crewmen wounded. Nevertheless, I did not have to encourage my crew and Mr Herbet, the officer on the forecastle, with the support of Sub-Lieutenant Lavergne, got together several men to make another attempt, but the two vessels broke their grapples and parted away from each other. During this time, the guns on both sides were firing and the forecastle officers threw several hand grenades. While the vessels were still together, we were fighting each other, grabbing lances or pistols from the hands of our opponents and maiming each other without needing to board. The enemy drifted further on our starboard side, actively firing at us broadside after broadside.

One of them tore away my arm and I encouraged my men by shouting: ‘Be brave, they are going to strike!’ I asked Mr Herbet, the last remaining lieutenant , to take over command of the vessel and he arranged transportation to my cabin. Time was now around 3am. Mr Herbet and Mr Lavergne encouraged the remaining men still alive to keep fighting, until two of our shots seemed to bring distress on board the enemy ship. As the commanding officer was shouting: ‘Cease fire, they have striked’, the schooner blew up at pistol range on our lee side. We were engulfed with flames and debris which were falling all around. The commanding officer ordered water to be thrown everywhere and asked to lower the launch to save the enemy crew who had survived the explosion, but it had been completely shattered and our aft davits destroyed. We saw three or four survivors swimming among the debris and we were able to shout to them to come to us. as we were unable to manoeuvre due to lack of wind. None was able to reach us, they shouted that they were blind. Time was 3:30am. Our first task was then to take care of the wounded, 31 of them, with only five dead.

Only 13 sailors were still not wounded, and we repaired the damage as much as we could, whilst aiming towards the French coast where we arrived on the 14th’. Signed for Captain Leroux by Jean Herbet, Lieutenant.

Captain Leroux, like four other crew members, died soon afterwards from his wounds. They were buried in Tréauville cemetery, within the Diellette Harbour Parish, where the cutter called to recover from its fight before sailing back to St. Malo.

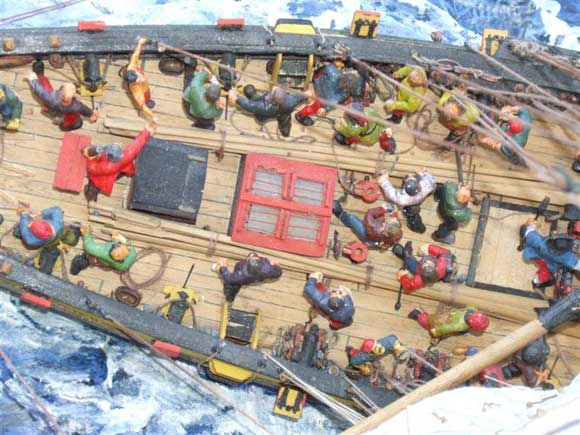

Pic 8: The model under construction. Pic 9: Full view of the diorama, note on the left side the transparent rod used to pull the sails up to simulate the wind force on the stay and top sails. Pic 10: At the stern, the impressive seaway has been made with some white paint. Note the helmsman looking up at the furling of the topgallant sail. Pic 11: A view of the wale chains, where one can see the very crude commode hole! Pic 12: A seagull view again, showing how the deck is crowded by crew, oars, spare spars and the guns.

The model

Ship modelling does not escape from modern day marketing! It was when pushing my caddy doing the chore of weekly shopping, that I stopped in front of a pile of Soclaine kits of Le Renard. Another miracle of our consumption society was soon to emerge and one of the kits quickly joined salads and milk bottles, whilst my mind started to wonder how to turn this model into a diorama. At the same time I started to think about the documentation I had to collect and how to set it up to bring as much life as possible to this model.

The first move was to read a magazine article in the French magazine Chasse Marée about the full-size replica, which has been built in St. Malo as part of the sailing ship revival frenzy that France has enjoyed in the last three decades. Beyond numerous details allowing me to improve significantly the quality and historical value of the model, I found there a challenging sentence under the sail plan of the replica. ‘The replica’s sail plan had to be very significantly reduced compared to the extraordinary sail plan of the Napoleonic period’. Although the full-size replica was built according to extensive historical data, it had as well to be able to carry the general public. She had to be able meet modern day safety regulations and to be economical and be managed by a crew of only three compared to the numerous and extremely well trained crew of the original vessel.

In the case of my model, things were quite different, as the only cruising ground was to be the living room, and the recruitment of a full crew is not a big issue at 1/50th scale. Taking this into account, I decided to build my model as close as possible to the historical reality of this type of vessel, reproducing the extreme sail plan of these cutters. Very interesting exchanges followed with one of the naval architects of the full-size replica, Thierry Echard, who forwarded me the sail plans of various 19th century cutters he had collected during his historical research and providing me as a bonus, detailed drawings of the different masts and spars, more than balancing the rather crude drawings provided with the kit. From all this data I decided to select as a baseline of the sail plan of my model, that of a 1800s customs cutter named Hauser, which was the most extreme of all the existing originals compiled by Thierry Echard.

This sail plan illustrates the ultimate technological limits of the sailing vessel of this era. The main limitations for these single mast vessels being the availability of a high quality pine tree trunk to make up the mast and the ability to cope with the very high stresses resulting on the hull. For these reasons, many of these vessels had a short life as cutters, and were later converted with smaller sails which required smaller masts and therefore a better distribution of the stresses along the hull. These extreme designs were mandatory to allow the privateers to either chase their prey or to make their escape from Royal Navy frigates.

Pic 13: The topmen furling the topgallant sail. Pic 14: Forward view, note the port anchor and its buoy, stowed in the mainstays. Pic 15: The topsail and the topgallant. Pic 16: A starboard view, showing Le Renard at full speed. Pic 17: A stern view. Note the shroud made of Milliput around the rudder post, to make it watertight. Pic 18: Overlay of the sail plan of the model compared to the one of the current full-size replica.

Historical search

The search for clues to stay true to the historic reality of the period (as far as it can be deduced from available sources) was not limited to the rigging. Many details not included or inaccurately reproduced in the kit have been either reviewed or subsequentially made from scratch. For example, to reward the risks taken with this extreme sail plan, I had to provide the crew with good quality food, but where to locate the galley? On the deck, already quite crowded, or below? Here again discussions with Thierry Echard saved the day, with the advice that the galley stove would be located below deck, under the forecastle. So the only thing to do from a modelling point of view, was to add a small chimney there. Other discussions addressed such items as the existence and location of the round shot storage racks, the forestay sail deckhorse, boom support, boat davits, etc. At the same time, based this time on the excellent monograph for another cutter, the French Navy Le Cerf, an additional touch of comfort and hygiene was brought to the model with very crude toilet facilities installed in the chain-wales.

Without the diesel engine provided on the full-size replica, my model like the original, had to be equipped with a set of oars to make her way in case of calm weather and to escape possible capture if need be. A dozen oars were therefore added on the model’s deck, together with some spare pieces of rigging. The deck was therefore quite crowded to the point that the small boat (that supplied in the kit was discarded and replaced by a scratchbuild version) had to be hung outside the hull on a pair of boat davits, although in his full report, the captain said that the boat was indeed stored on deck.

A much improved model kit

The kit from Soclaine is a good basis for a model, especially with regard to the hull, but the proposed deck made of plywood with a printed simulation of the planking was considered far too crude and was discarded. The deck has been made with small planks, whose edges have been tainted with black to simulate the pitch. The set of sails supplied in the kit were also discarded because they were far too small, but also because they looked horrible. The sails were therefore made from a piece of fine cotton, reproducing not only the fabric, but the bolt ropes as well, before discolouring them with a dye to give them a well worn look.

The artillery was carefully reviewed, the main change being to implement the reproduction of the four 4pdr. guns mentioned in the captain’s report, giving our privateer an extra long distance firepower capability. Taking care of the rigging was a major task, the 1/50th scale allowing me to reproduce amongst other things, the detail of the standing rigging and the different rope thicknesses. With all this detailing added, the model has evolved from a basic model kit to a real ship model. A specific effort was made to make the sails as close as possible to real life. Once set up on the model, it was fixed sideways on a rotating vice and the sails were soaked with a mixture of water and glue, then loaded by a handful of lead shots and left to dry overnight. The results was a very effective ballooning effect, simulating the pressure of the wind. The same technique was used to load and keep in a natural hanging effect all the ropes of the rigging, using little weights to curve them.

The diorama

I am always amazed by the size of the crew required to man vessels of the Napoleonic era, so apart from the full sail plan, I decided to represent the model on a diorama with the whole crew on board. To add a little drama to the diorama, I considered that a vessel had just been sighted (possibly the Alphea) and that the crew were all excited and preparing to fight, while at the same time the wind is strengthening and the topmen are urgently furling the topgallant sail.

The crew on a vessel which is only 60ft long and 16ft wide was no less than 49 officers, gunners and sailors, and these have been made from modified figures of the Warhammer Series, which have the advantage of providing very lively postures and many possible combinations of heads, legs, arms and torsos.

The full-hull model is set on a rectangular base which has been covered with a layer of plaster to simulate the sea surface. To reduce as much as possible the footprint of the diorama, the hull has been placed on one of the diagonals, with the wind coming from the aft quarter, so that the sails are pushed sideways and do not impair the view of the busy deck.

Bibliography and other sources

Apart from the drawings provided in the kit, I have extensively used the monograph on Le Cerf, a French Navy Cutter of the period available at Ancre (wwww.ancre.fr). With regard to the crew, one of Osprey (Elite 74) books is dedicated to pirates and privateers. But most importantly, one can contact the Association du Cotre Corsaire, Grande Porte Tour Ouest BP165, 35408 Saint Malo and easily cross the Channel from England to spend a day or two on the full-size replica.